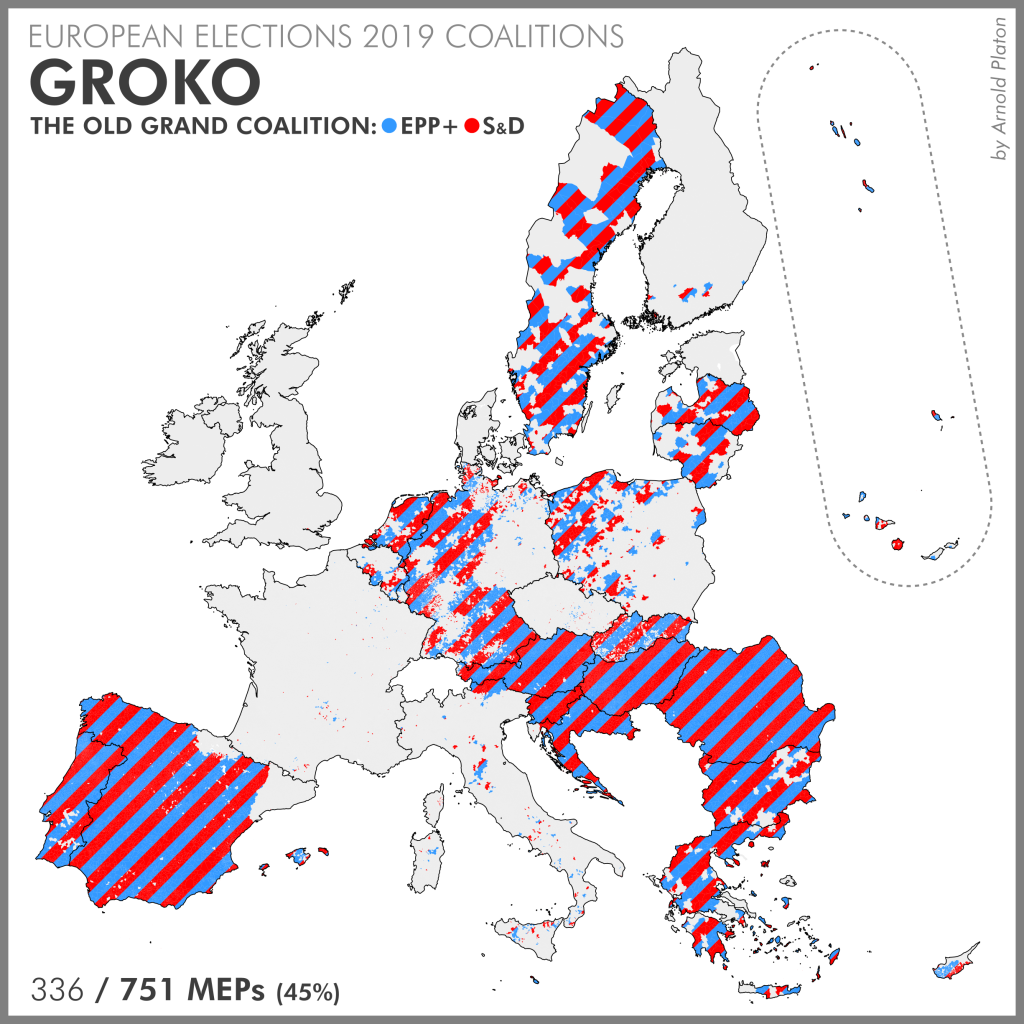

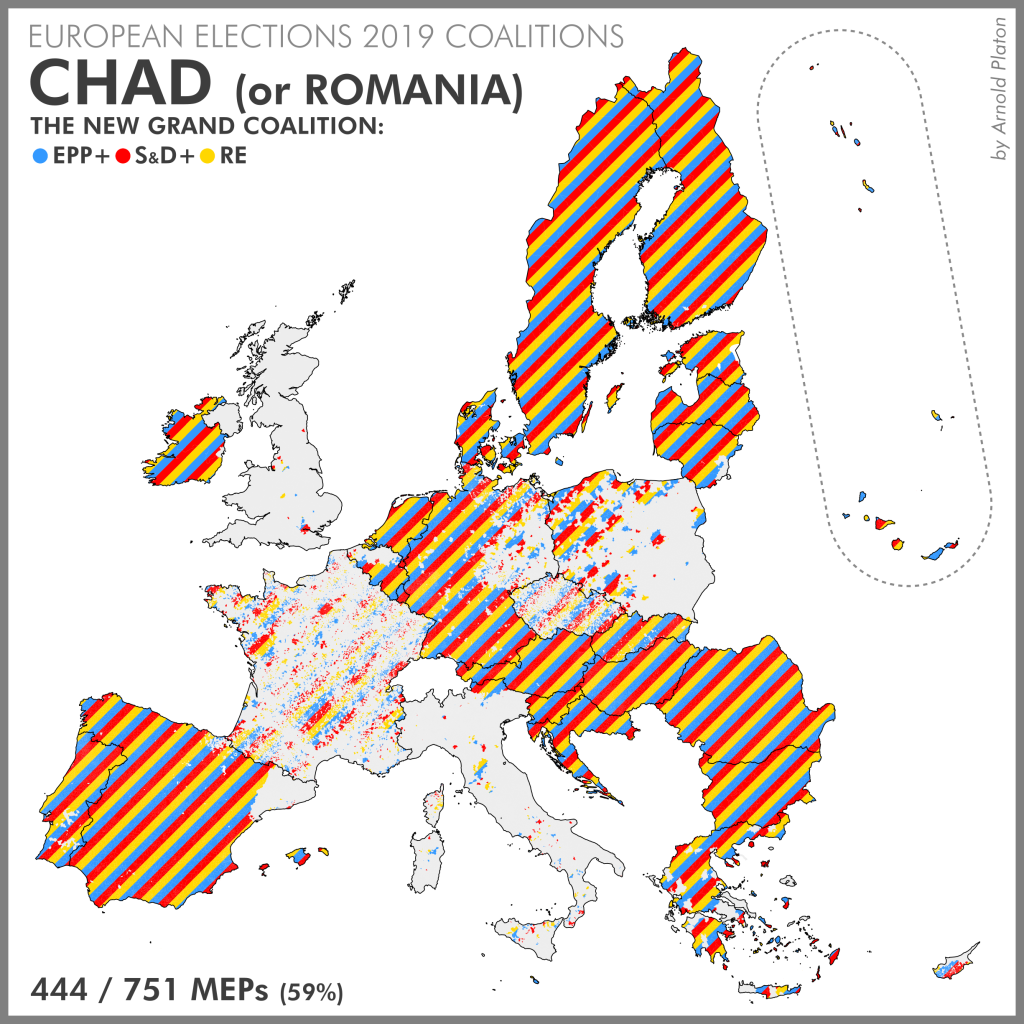

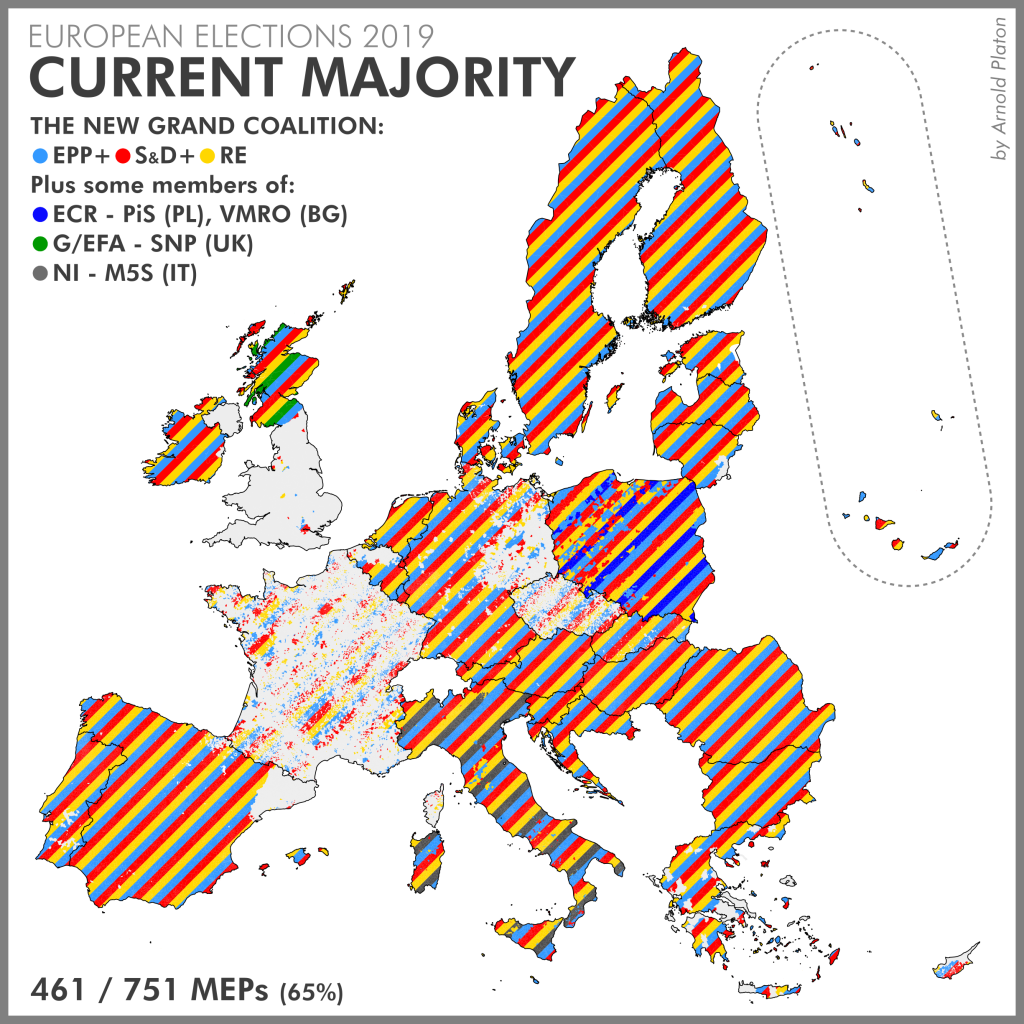

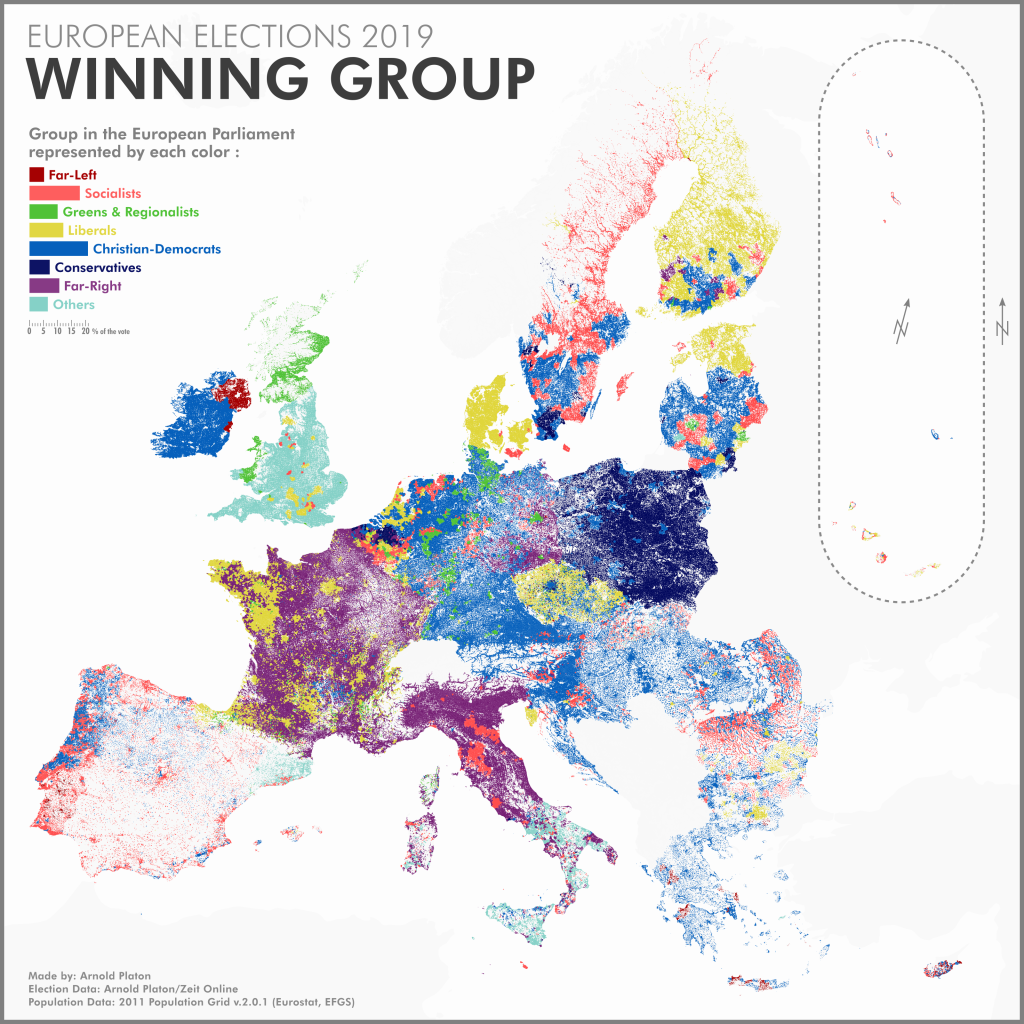

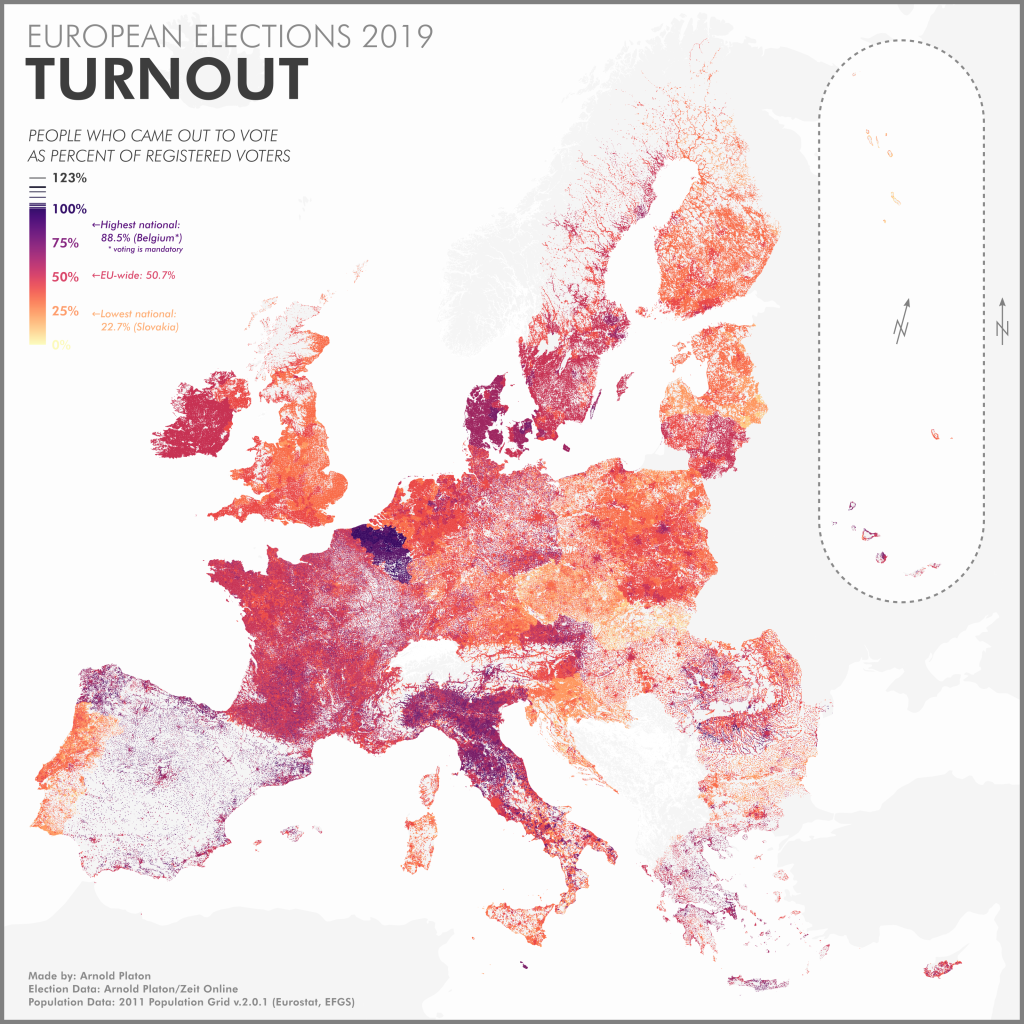

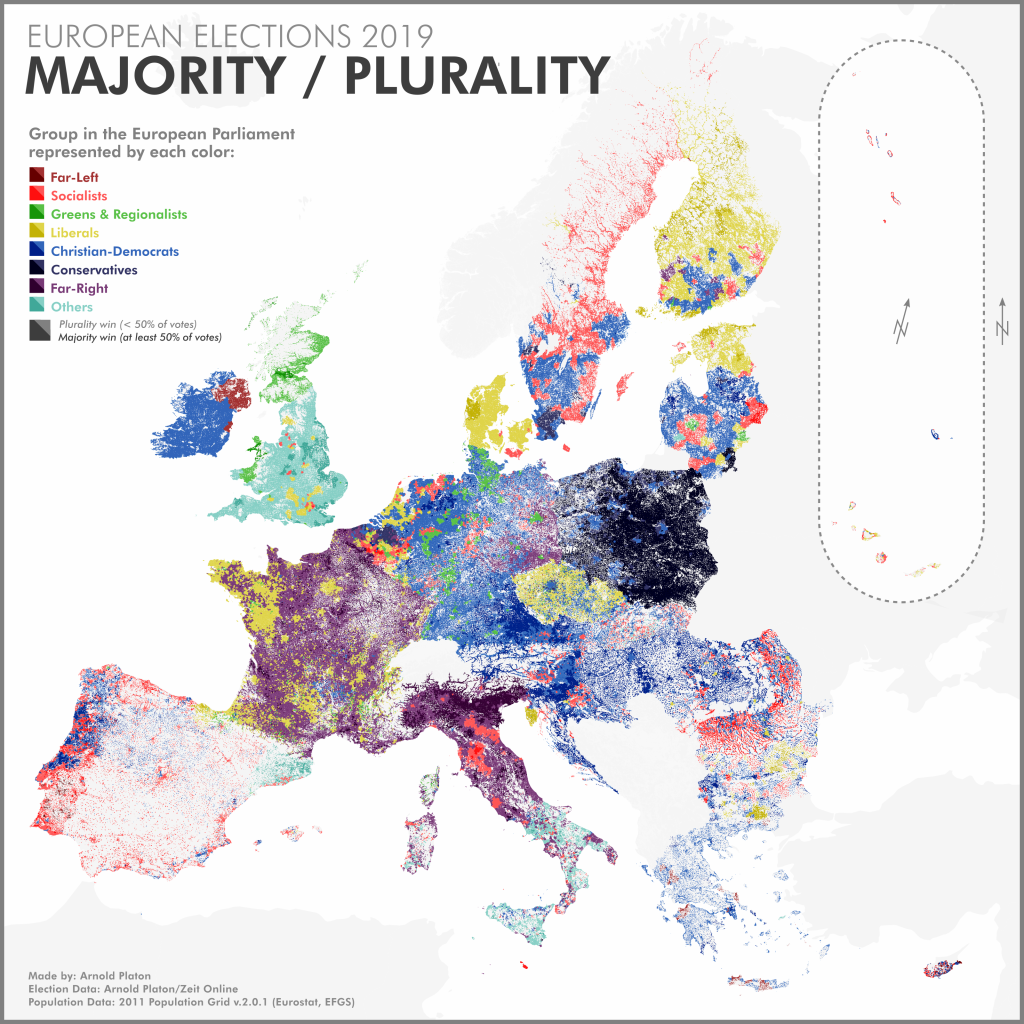

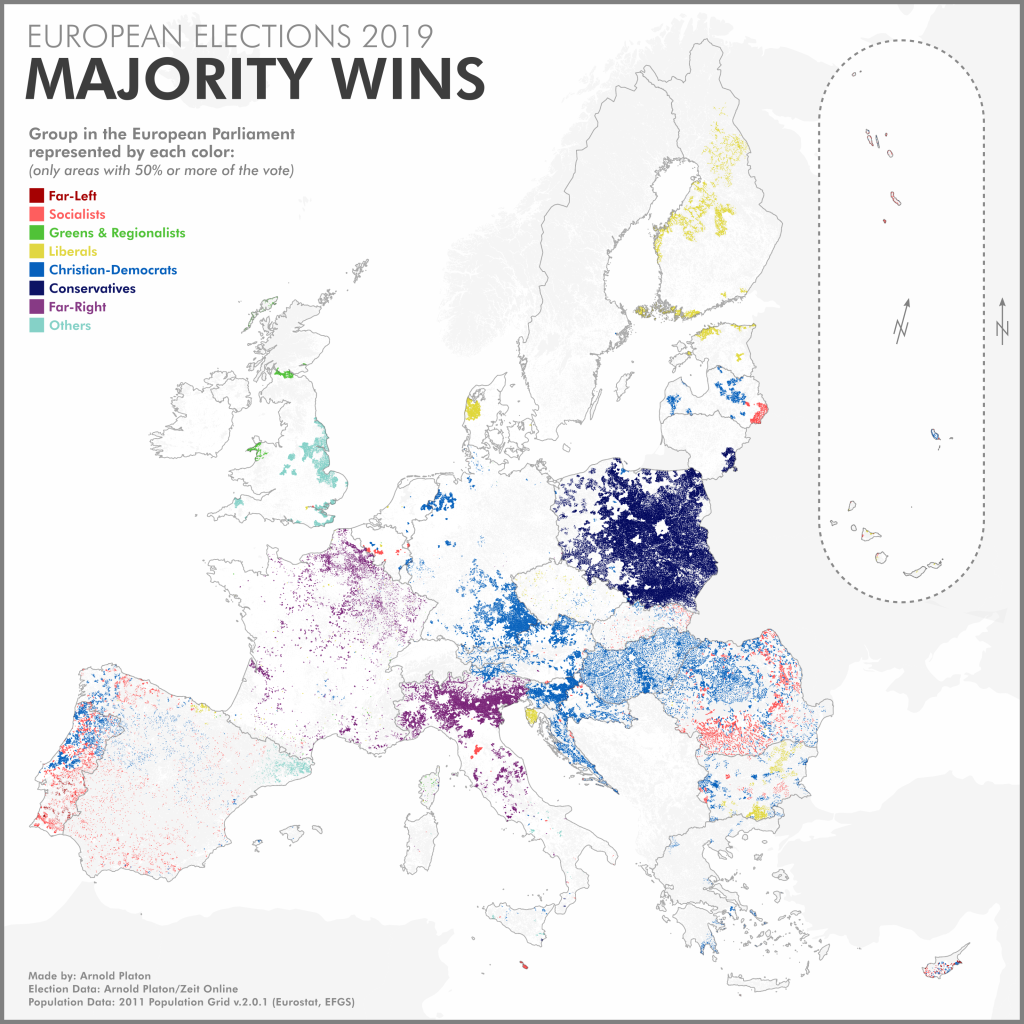

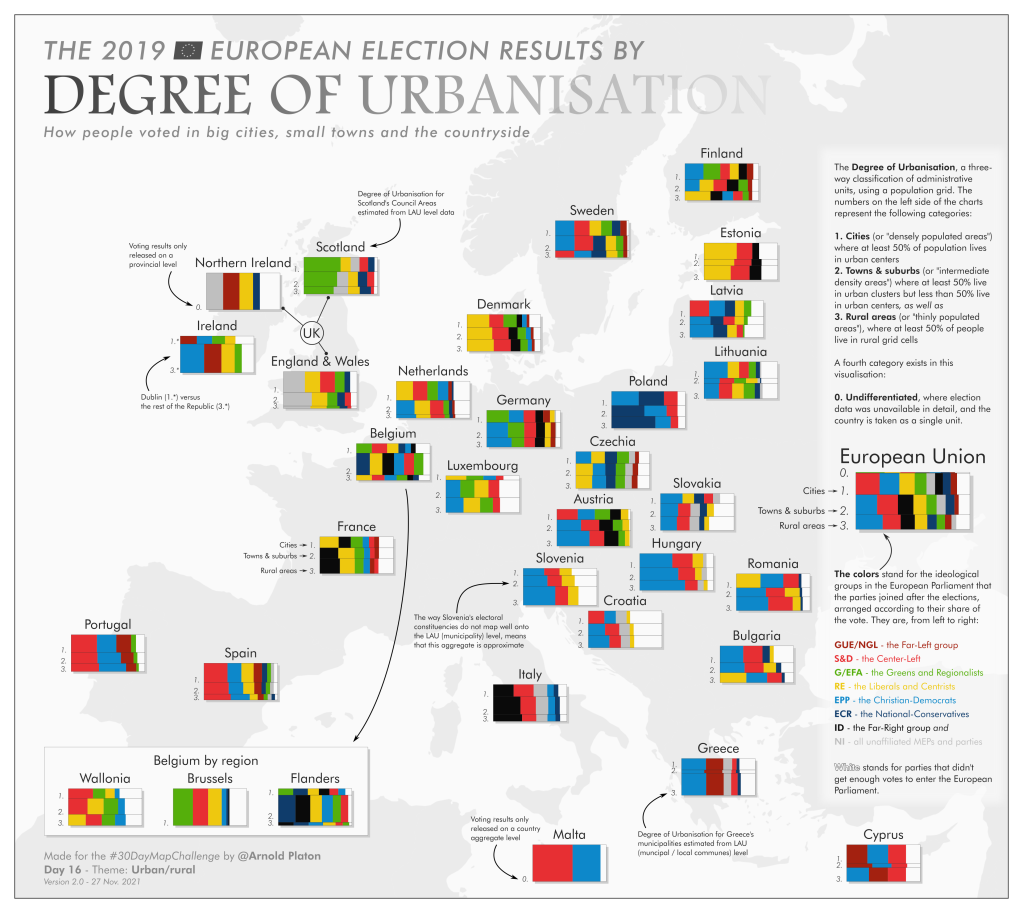

Because people in urban, suburban and rural areas often vote in slightly different ways, I decided to map the results of the 2019 European Elections split by what Eurostat calls “Degree of Urbanisation” (or “DegUrba” for short). It’s a standardized EU indicator that uses the population grid to classify Local Administrative Units, “LAU” for short, (i.e. municipalities of member states) into three types of area:

- 1. Cities (densely populated areas)

- 2. Towns and suburbs (intermediate density areas)

- 3. Rural areas (thinly populated areas)

As with all of my European Election maps and visualizations, the election data is grouped by European Parliament Groups, as they were at the inaugural session of the new parliament.

Some notes on various countries and design choices:

Ireland – election data was available only by electoral constituency. This forced me to frame the visualization as a Dublin (city) versus the rest of the country (rural).

Malta & Northern Ireland (UK) – election data only available agregated for the whole country / province.

Greece – election data is available by Municipalities (325 in total) but DegUrba data is available by LAU (6133 in total, in Greece, below municipalities). I aggregated the DegUrba to Municipality level by looking at the dominant category but I’m not sure methodology is 100% watertight.

Scotland – election data by Council Areas (32) but DegUrba data by LAU (41). While about half of the LAU map onto Council areas, the rest do not, although the boundary differences aren’t that big, and I’m pretty confident the guesstimated DegUrba level is correct.

Slovenia – election data was only available by electoral constituency (88 in total) which do not map well onto municipalities. As with Greece, I used an aggregate and estimate approach.

Belgium – Since the political landscapes are so different between Flanders and Wallonia, I decided to split it by regions as well, because the country aggregate to me makes little sense.

Made with Python (Svgwrite) and Inkscape, for the “30 Day Map Challenge” of 2021 (my only contribution)